In 1988, Morten Hansen landed his dream job as a management consultant. Eager to succeed, he followed what he thought was a wise strategy. He would outperform his co-workers by working very long hours.

Over the next three years, he worked anywhere from 60 to 90 hours each week. To maintain this intense schedule, he fueled himself with an endless supply of coffee and chocolate.

One day, Hansen stumbled upon the work of one of his colleagues named “Natalie” (not her real name). As he read her work, he realized her analysis was crisper, more compelling, and easier to understand than his work.

He went to look for Natalie one evening. However, she was not there. He asked a colleague where she was. His colleague told him that Natalie had already gone home for the day. She always worked from 8:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. She never worked late. She did not work on the weekends either.

Both Morten and Natalie had the intelligence and drive required to work at a top-tier consulting firm. They also had a similar amount of experience. However, Natalie produced better work than Morten, while working fewer hours. He wondered how that could happen.

“The Natalie Question”

A few years later, Hansen left consulting to pursue an academic career. After earning his PhD from Stanford University, he became a professor at Harvard Business School. He often found himself thinking about what he called “the Natalie question.” Why had she been able to perform better than him, while working less?

His curiosity inspired him to focus his research on corporate performance. Starting in 2002, he and Jim Collins worked for 9 years on a book called Great by Choice, a sequel to Jim’s Good to Great. Both books provide research-based frameworks for great performance in companies.

Hansen was still curious, though, about what led to great performance by individuals. In 2011, he launched one of the most robust research projects ever conducted on individual performance at work.

He recruited a team of researchers and began developing a set of theories about which behaviors led to higher work performance. He also reviewed more than 200 relevant academic studies and leveraged insights from over 100 interviews with business professionals.

In addition, Hansen and his team tested some of their theories in a study of 5,000 managers and employees across a variety of industries, job functions, and seniority levels. The findings from this research eventually led Hansen to write Great at Work: How Top Performers Do Less, Work Better, and Achieve More.

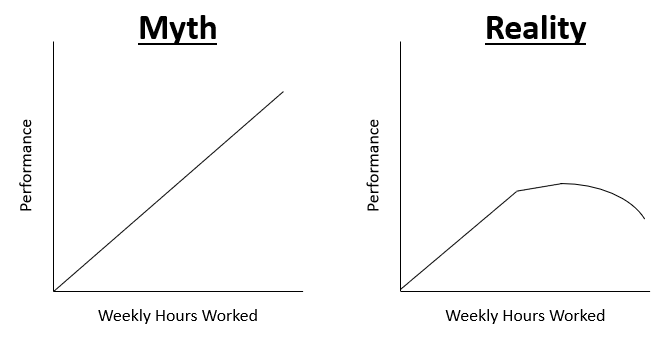

One of the factors Hansen and his team examined in their study was number of hours worked per week. They found that working longer hours enhances performance, but only to a point. Here are some of their findings:

- Performance increased as the number of hours worked rose from 30 to 50 per week.

- Performance flattened as the number of hours worked rose from 50 to 65 per week.

- Performance declined as the number of hours worked exceeded 65 per week.

Hansen likens the study’s data to squeezing juice from an orange. At first, squeezing an orange produces a lot of juice. Then, as you keep squeezing, you stop getting much more juice. Eventually, there is a point where you are squeezing as hard as you can, yet producing no extra juice.

While Hansen’s research has found that performance typically flattens and then declines when someone works more than 50 hours each week, the exact number may vary depending on the person, the job, and other factors.

The key message is that there is a point at which working longer adds minimal value, and another at which it becomes counterproductive. We can debate how many hours of work it takes to reach each of these points. However, there is no debate that each of these points exists. These points occur sooner than many advisors realize.

Many advisors buy into the Work Longer Myth that the longer you work, the better you perform. In reality, there is a point at which performance flattens and another at which it actually declines. See image below. (Credit to Morten Hansen for inspiring this image.)

Summary and Final Thoughts

How many hours should you work each week?

It depends. While studies have found that performance flattens and then declines once you work over 50 hours each week, that number could change based on the person, the job, and other factors.

If you work incredibly long hours, you might think your hours are one of the keys to your success. In reality, as discussed here, you might actually be able to unlock an even higher level of performance by working less. Stronger hours (not longer hours) are the key to achieving and sustaining higher performance over the long-term.

References

- Hansen, Morten. Great at Work: How Top Performers Do Less, Work Better, and Achieve More. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

About the Author

Pete Leibman is a speaker and author who helps professional services firms sustain high performance. His clients include leading law firms, consulting firms, and financial services firms. He also speaks at top universities and at conferences for professional associations. Pete is the author of three books and more than 300 articles on high performance. His latest book (due out in April 2026) is Stronger Advisor: High-Performance Habits for Consultants, Lawyers, and Advisors.

Schedule a Call with Pete

Let’s discuss a keynote, workshop, or program to help your firm sustain high performance.